アクター

`アクターモデル`は並行分散システムを作るための高度な抽象を提供します。アクターモデルを用いることで開発者は明示的なロックやスレッドの管理を行う労力を軽減した上で信頼性のある並行並列なシステムを作ることができます。アクターは Cal Herwitt が1973年に論文として発表したものですが、Erlangによって世に広められ、この成功例として Ericsson 社による高い並行性と信頼性を持つ電気通信システムの構築が挙げられます。

Akka のアクターは Erlang からシンタックスを拝借した Scala のアクターと似ています。

アクターの生成

注釈

Akka では全てのアクターが親となるアクターに監視され、同時に子供のアクターの supervisor になる(可能性がある)という方式をとっています。この方式については Actor Systems や Supervision and Monitoring あるいは Actor References, Paths and Addresses といった記事を参考に読んでみるとよいでしょう。

アクターのクラスを定義する

アクターは:class:`Actor`という基本traitを拡張することで実装することができます。また、ここで:meth:`receive`というメソッドを実装する必要があります。:meth:`receive`というメソッドはcase文の塊で(この型は`PartialFunction[Any, Unit]``です)、Scalaのパターンマッチングを使ってアクターがどのようなメッセージを処理できるかということとそのメッセージがどのように処理されるかということを定義します。

以下はこのサンプルコードです。

import akka.actor.Actor

import akka.actor.Props

import akka.event.Logging

class MyActor extends Actor {

val log = Logging(context.system, this)

def receive = {

case "test" => log.info("received test")

case _ => log.info("received unknown message")

}

}

Akkaのアクターの``receive``メッセージループは網羅的であるということに注意してください。これはErlangやScala言語組み込みのアクターとは異なっています。つまり受け取ることのできる全てのメッセージについてのパターンマッチを書く必要があり、未知のメッセージを処理したい場合はデフォルトのcaseを書かなければいけません。これを行わなかった場合は ``ActorSystem``の``EventStream``に`akka.actor.UnhandledMessage(message, sender, recipient)``が発行されます。

また、振る舞いの戻り値の型が``Unit``であることにも注意してください。アクターが受け取ったメッセージに対して応答を返す場合、後で説明するようにこれを明示的に行う必要があります。

:meth:`receive`メソッドの結果は部分関数であり、アクターの"初期の振る舞い"とみなされます。アクターが生成された後でどのように振る舞いを変えるかということについての詳しい情報は`Become/Unbecome`_を参照してください。

Props

:class:`Propsはアクターを生成するときのオプションを指定するための設定クラスです。このクラスのインスタンスは不変なので気軽に共有することができるアクターを生成するためのレシピと考えることができます。また、このレシピにはデプロイに関係した情報(例えばどのdispatcherを使うかとかいったもの)も含めることができます。

import akka.actor.Props

val props1 = Props[MyActor]

val props2 = Props(new ActorWithArgs("arg")) // careful, see below

val props3 = Props(classOf[ActorWithArgs], "arg") // no support for value class arguments

二つ目のやり方は生成する:class:`Actor`にどのように引数を渡すかということを例示していますが、後で説明するように、アクターの外側のみで用いるべきやり方です。

最後のやり方はアクターのコンストラクタに引数を渡す場合にどのようなコンテクストでも使うことができるやり方です。Propsオブジェクトの中でどのコンストラクタを用いるべきかということを調べて、適当なコンストラクタが見つからなかった場合や複数のコンストラクタにマッチしてしまった場合には:class:IllegalArgumentException となってしまいます。

注釈

アクターのコンストラクタが引数として値クラスを受け取る場合、アクターの:class:`Props`を作るための推奨される手法はサポートされていません。

危険な方法

// NOT RECOMMENDED within another actor:

// encourages to close over enclosing class

val props7 = Props(new MyActor)

このメソッドはアクターの中で使わないほうがいいです。このメソッドによって呼び出し元のアクターのスコープをリークしてしまい、:class:`Props`が永続化不可になってしまい競合状態(アクターのカプセル化が壊されるということ)を引き起こす可能性があります。将来的にはマクロを使って同じようなシンタックスを使っても問題が起きないようにする予定ですが、現在のところこの方式は非推奨としたほうがいいでしょう。一方で、"推奨される手法"のところに書いてあるアクターのコンパニオンオブジェクトにある:class:`Props`のファクトリを使うというやり方は特に問題がありません。

このメソッドを使うユースケースは二つあります。一つはアクターのコンストラクタに引数を渡したい場合ですが、これは新しくできた:meth:`Props.apply(clazz, args)`を上に書いてあるとおりに使うか下に書いてあるような推奨される手法を使うことで解決できます。もう一つは"その場で"無名のアクターを作る場合ですが、これはそのようなアクターにちゃんと名前を付けてあげることで解決できます。(アクターがトップレベルの``object``として宣言されていない場合、それに紐づくインスタンスの"this"の参照がクラスの最初の引数に渡されてしまいます)

警告

あるアクターを別のアクターの中で宣言することは非常に危険でアクターのカプセル化を破壊してしまいます。アクターの"this"への参照を:class:`Props`に渡してしまわないように注意してください。

エッジケース

:class:`Props`を使ったアクターの生成には二つのエッジケースがあります。

引数に:class:`AnyVal`を受け取るアクター

case class MyValueClass(v: Int) extends AnyVal

class ValueActor(value: MyValueClass) extends Actor {

def receive = {

case multiplier: Long => sender() ! (value.v * multiplier)

}

}

val valueClassProp = Props(classOf[ValueActor], MyValueClass(5)) // Unsupported

デフォルトのコンストラクタ引数を持つアクター

class DefaultValueActor(a: Int, b: Int = 5) extends Actor {

def receive = {

case x: Int => sender() ! ((a + x) * b)

}

}

val defaultValueProp1 = Props(classOf[DefaultValueActor], 2.0) // Unsupported

class DefaultValueActor2(b: Int = 5) extends Actor {

def receive = {

case x: Int => sender() ! (x * b)

}

}

val defaultValueProp2 = Props[DefaultValueActor2] // Unsupported

val defaultValueProp3 = Props(classOf[DefaultValueActor2]) // Unsupported

どちらのケースもコンストラクターを見つけられない状態になってしまって IllegalArgumentException がスローされます。

次のセクションでは:class:`Actor`のpropを作るための推奨される手法を説明します。同時にこの手法はこれらのエッジケースに対する回避策になります。

推奨される手法

全ての:class:`Actor`のコンパニオンオブジェクトの中で:class:`Props`の生成を適切に行うことを補助するようなファクトリメソッドを提供するのは良いアイディアです。コンパニオンオブジェクトの中のコードブロックはcall-by-nameなメソッド引数の中にリークしないので、こうしたファクトリメソッドを使えば``Props.apply(...)``を使うことによる落とし穴に嵌ることを避けることができます。

object DemoActor {

/**

* Create Props for an actor of this type.

*

* @param magicNumber The magic number to be passed to this actor’s constructor.

* @return a Props for creating this actor, which can then be further configured

* (e.g. calling `.withDispatcher()` on it)

*/

def props(magicNumber: Int): Props = Props(new DemoActor(magicNumber))

}

class DemoActor(magicNumber: Int) extends Actor {

def receive = {

case x: Int => sender() ! (x + magicNumber)

}

}

class SomeOtherActor extends Actor {

// Props(new DemoActor(42)) would not be safe

context.actorOf(DemoActor.props(42), "demo")

// ...

}

もう一つの良い手法として、コンパニオンオブジェクトの中でそのアクターが受け取ることができるメッセージを宣言するというものがあります。このようにしておくと、アクターがどのようなメッセージを受け取ることができるのかがわかりやすくなります。

object MyActor {

case class Greeting(from: String)

case object Goodbye

}

class MyActor extends Actor with ActorLogging {

import MyActor._

def receive = {

case Greeting(greeter) => log.info(s"I was greeted by $greeter.")

case Goodbye => log.info("Someone said goodbye to me.")

}

}

Propsを使ったアクターの生成

アクターは:class:`Props`のインスタンスを:class:`ActorSystem`や:class:`ActorContext`が持っている:meth:`actorOf`というファクトリメソッドに渡すことで生成できます。

import akka.actor.ActorSystem

// ActorSystem is a heavy object: create only one per application

val system = ActorSystem("mySystem")

val myActor = system.actorOf(Props[MyActor], "myactor2")

:class:`ActorSystem`を使うとトップレベルのアクターを生成できます。トップレベルのアクターはアクターシステムが提供しているガーディアンアクターによって監視されます。一方でコンテクストから生成したアクターはそのアクターの子アクターになります。

class FirstActor extends Actor {

val child = context.actorOf(Props[MyActor], name = "myChild")

// plus some behavior ...

}

子供から孫といった階層を作るようにしてください。そのようにすることでアプリケーションの論理的なエラー処理の構造を作ることができます。詳しくは:ref:`actor-systems`を参照してください。

:meth:`actorOf`を呼ぶことで:class:`ActorRef`のインスタンスを得ることができます。:class:`ActorRef`はアクターのインスタンスとつながっていて、アクターと対話するための唯一の手段となります。:class:`ActorRef`は不変でそれが表現しているアクターと一対一の関係を持っています。:class:`ActorRef`は永続化可能なのでネットワークを介することができます。つまり、シリアライズしたインスタンスをリモートのホストに送信した場合、元のノードのアクターをネットワークを超えて表現することができます。

nameパラメータはオプションですがアクターには名前を与えた方がよいでしょう。なぜなら、アクターの名前はログメッセージでアクターを識別するために用いるからです。アクターの名前は空文字や"$"から始まる文字列は許可されていませんが、そうした名前がURLにエンコードされた文字には含まれることがあります。(例えば、"%20"は空白文字です。)もじ与えられた名前が既に同じ親を持つ他の子アクターが利用していた場合、:class:`InvalidActorNameException`がスローされます。

アクターは生成されたら非同期に自動的に開始されます。

コンストラクタ引数の値クラス

アクターのpropsのインスタンスを得るための推奨される方法ではアクターのどのコンストラクタを呼ぶのが正しいのかを調べるためにリフレクションを使っています。この技術的な制限のため、値クラスを引き数として受け取るコンストラクタの利用はサポートされていません。こういったケースでは値クラスの中の値をあらかじめ取り出しておくかコンストラクタを直接呼び出すようなpropsを作る必要があります。

class Argument(val value: String) extends AnyVal

class ValueClassActor(arg: Argument) extends Actor {

def receive = { case _ => () }

}

object ValueClassActor {

def props1(arg: Argument) = Props(classOf[ValueClassActor], arg) // fails at runtime

def props2(arg: Argument) = Props(classOf[ValueClassActor], arg.value) // ok

def props3(arg: Argument) = Props(new ValueClassActor(arg)) // ok

}

依存性の注入

アクターがコンストラクタで引数を受け取る場合、`すでに述べたように`__それは:class:`Props`の生成の中で利用する必要があります。しかし、ファクトリメソッドを用意していたとしても直接コンストラクタを使うケースがあります。例えば依存性の注入を行うフレームワークがコンストラクタの引数を調べる場合です。

import akka.actor.IndirectActorProducer

class DependencyInjector(applicationContext: AnyRef, beanName: String)

extends IndirectActorProducer {

override def actorClass = classOf[Actor]

override def produce =

// obtain fresh Actor instance from DI framework ...

}

val actorRef = system.actorOf(

Props(classOf[DependencyInjector], applicationContext, "hello"),

"helloBean")

警告

:class:`IndirectActorProducer`が必要な時に``lazy val``などを使って常に同じインスタンスを得たいと思うかもしれません。しかし、同じアクターのインスタンスを使いまわすということはは:ref:`supervision-restart`で述べてるようなアクターの再起動といった概念と衝突するためサポートされていません。

依存性の注入を行うフレームワークを使う場合、アクターのbeanはシングルトンスコープであることは*許可されません*。

依存性の注入のためのテクニックや依存性注入を行うフレームワークとの統合については`Using Akka with Dependency Injection <http://letitcrash.com/post/55958814293/akka-dependency-injection>`_ guidelineやLightbend Activatorの中の`Akka Java Spring <http://www.lightbend.com/activator/template/akka-java-spring>`_ tutorialにより詳しい情報があります。

Inbox

アクターの外側のコードからアクターと通信をする場合、``ask``パターン(後で出てきます)を使うのが一つの方法ですが、それを使えない場合が二つあります。一つは複数のメッセージを受け取るような場合(例えば通知サービスとして実装されている:class:`ActorRef`を購読する場合)で、もう一つはActorのライフサイクルをwatchしている場合です。こういった場合のために:class:`Inbox`というクラスが用意されています。

このコードでは:class:`Inbox`から:class:`Inbox`への暗黙的な変換が行われています。つまりこの例ではsenderへの参照は暗黙的に:class:`Inbox`に対するものになります。このようにすることで最後の行に書かれているようなやり方で応答を受け取ることができます。アクターをwatchする方法も簡単です。

Actor API

Actor traitには、抽象メソッドが一つしか定義されていません。それはすでに述べた:meth:`receive`メソッドで、アクターの振る舞いを実装するメソッドです。

現在のアクターの振る舞いが受け取ったメッセージを処理できない場合、:meth:`unhandled`が呼ばれ、そのデフォルトの実装では``akka.actor.UnhandledMessage(message, sender, recipient)``をアクターシステムのイベントストリームに発行します(これは``akka.actor.debug.unhandled``という設定を``on``にすることで実際のデバッグのメッセージに変換されます)。

Actor traitには他にも以下のようなメソッドがあります。

selfこのアクター自身の:class:`ActorRef`への参照sender最後に受け取ったメッセージの送信者となるActorへの参照。通常:ref:`Actor.Reply`で述べているような用途で使います。supervisorStrategyユーザがオーバーライド可能な子アクターをどう監視するかというストラテジーの定義このストラテジーは戦略を決めるための関数の中でアクターの内部状態にアクセスするため、通常アクターの中で宣言します。障害は supervisor にメッセージとして通知され、他のメッセージと同じように処理されます。(通常の振る舞いの外側に置かれるものの)この関数の中ではアクター内部の全ての値や変数、"sender"への参照を利用することができます。(これは直接の子アクターが報告した障害の情報に含まれます。元となる障害が孫以上の子孫の場合でも障害が起きた階層の sender が報告されます。)

contextアクターや現在のメッセージに関するコンテクスト情報を参照できます。これには以下のようなものがあります。子アクターを作るためのファクトリメソッド(

actorOf)アクターが所属しているシステム

supervisorである親アクター

監視している子アクター

ライフサイクルの監視

:ref:`Actor.Hotswap`に書かれている動的に置き換え可能な振る舞いのスタック

:obj:`context`のメンバーをimportすることで"context"というプレフィックスなしにそのメンバにアクセスすることができます。

class FirstActor extends Actor {

import context._

val myActor = actorOf(Props[MyActor], name = "myactor")

def receive = {

case x => myActor ! x

}

}

ここまででまだ残っているアクセス可能なメソッドはユーザがオーバーライドすることで以下の述べるアクターのライフサイクルにフックすることができるメソッドです。

ここまでに紹介した実装は:class:Actor traitを使うことでデフォルトで利用できます。

アクターのライフサクル

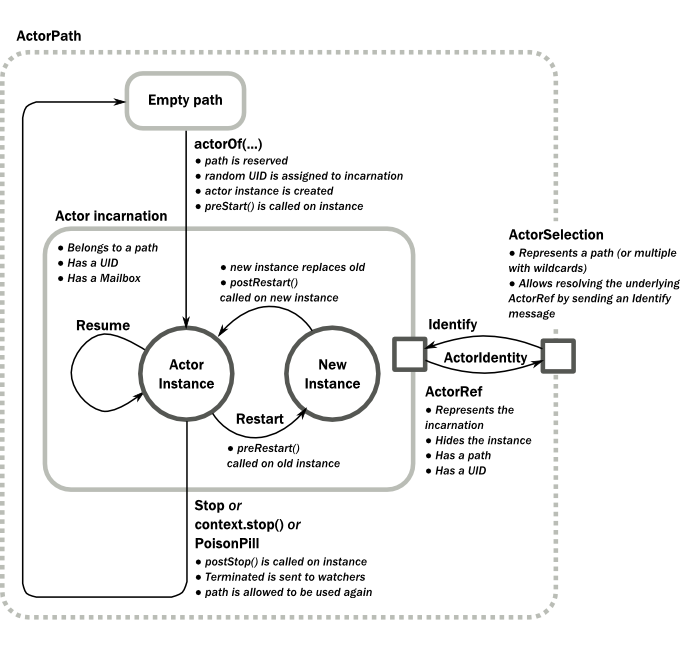

アクターシステムにおけるパスは生存しているアクターによって占有されている"場所"を表現しています。始めは(システムによって初期化されたアクターを除き)パスは空になっています。 actorOf() を呼びだすと Prop で表現されたアクターの*インカーネーション*が与えられたパスに生成されます。アクターのインカーネーションはパスと UID によって識別されます。再起動が行われたときには Actor のインスタンスは置き換えられますが、インカーネーションの方は置き換えられないので UID は同じものになります。

アクターのインカーネーションのライフサイクルはアクターが停止した時に終わります。この時、これに対応したライフサイクルの終了イベントが呼ばれ、これを watch しているアクターに停止が通知されます。インカーネーションが停止したのち、インカーネーションのパスは再び actorOf() を使って再利用することができるようになります。この場合新しいインカーネーションの名前は前のものと同じですがUIDは別のものになります。アクターは自分自身や他のアクター、あるいは``ActorSystem``によって停止されることがあります。(:ref:`stopping-actors-scala`を参照)

注釈

アクターは参照されなくなったとしても自動的に停止することはないという点は重要です。生成された全てのアクターは明示的に破棄する必要があります。ただし親のアクターを停止する場合、そのアクターが生成した全ての子供のアクターも停止されるのでこの点は単純です。

``ActorRef``はただ単に与えられたパスを表現しているのではなくいつでもインカーネーション(パスとUID)を表現しています。つまりアクターを停止して同じ名前のアクターを生成した場合、新しく生成した``ActorRef``は古いインカーネーションでなく新しいインカーネーションを指しています。

一方で ActorSelection はパスを示していて(ワイルドカードを使った場合は複数のパスを指します。)、現在そのパスを持っているのがどのインカーネーションなのかを完全に識別することができます。このため ActorSelection を watch することはできません。パスに存在するインカーネーションを watch するためには、ActorSelection に対して Identity メッセージを送信し ActorSelection から応答として ActorIdentity を受け取り、その中に含まれる正しい参照(actorSelection-scala`を参照)を使って現在のインカーネーションの ``ActorRef` を解決します。 ActorSelection が持つ resolveOne を使うとパスにマッチした ActorRef の Future が戻されるので同じようなことができます。

ライフサイクルの監視、DeathWatch

他のアクターの停止を知るために(例えば、永久に停止された場合や一時的ではない障害によって再起動された場合など)、アクターは他のアクターが停止時に発する Terminated メッセージを受け取るようにすることができます。(Stopping Actors`_も参照のこと)この機能はアクターシステムの :class:`DeathWatch というコンポーネントによって提供されています。

モニターを登録するのは簡単です。

import akka.actor.{ Actor, Props, Terminated }

class WatchActor extends Actor {

val child = context.actorOf(Props.empty, "child")

context.watch(child) // <-- this is the only call needed for registration

var lastSender = context.system.deadLetters

def receive = {

case "kill" =>

context.stop(child); lastSender = sender()

case Terminated(`child`) => lastSender ! "finished"

}

}

Terminated メッセージは登録や停止がどのような順番で起きたかとは独立して生成されることに注意してください。典型的な例として、監視を行うアクターは例え監視の登録を行った時点ですでに監視対象のアクターが停止されていたとしても Treminated メッセージを受け取ることになります。

監視の登録を複数回行うことが必ずしも複数のメッセージを作ることになるわけではありませんが、こうしたメッセージを正確に一度受け取ることができる保障はありません。監視対象のアクターの停止メッセージが作られてキューに入ってから、このメッセージが処理される前に他のところで登録が行われたら、二つ目のメッセージがキューに入ります。何故なら既に停止したアクターの監視を登録すると、直ちに: class:Terminated が生成されるためです。

同じようなことが他のアクターの生存監視を context.unwatch(target) を使ってやめた場合にも起こりえます。これは例え Terminated メッセージがメールボックスに入っていたとしても、unwatch`の呼び出しの後には監視を停止したアクターの :class:`Terminated メッセージは処理されないためです。

Start Hook

Right after starting the actor, its preStart method is invoked.

override def preStart() {

child = context.actorOf(Props[MyActor], "child")

}

This method is called when the actor is first created. During restarts it is

called by the default implementation of postRestart, which means that

by overriding that method you can choose whether the initialization code in

this method is called only exactly once for this actor or for every restart.

Initialization code which is part of the actor’s constructor will always be

called when an instance of the actor class is created, which happens at every

restart.

Restart Hooks

All actors are supervised, i.e. linked to another actor with a fault handling strategy. Actors may be restarted in case an exception is thrown while processing a message (see Supervision and Monitoring). This restart involves the hooks mentioned above:

The old actor is informed by calling

preRestartwith the exception which caused the restart and the message which triggered that exception; the latter may beNoneif the restart was not caused by processing a message, e.g. when a supervisor does not trap the exception and is restarted in turn by its supervisor, or if an actor is restarted due to a sibling’s failure. If the message is available, then that message’s sender is also accessible in the usual way (i.e. by callingsender).This method is the best place for cleaning up, preparing hand-over to the fresh actor instance, etc. By default it stops all children and calls

postStop.The initial factory from the

actorOfcall is used to produce the fresh instance.The new actor’s

postRestartmethod is invoked with the exception which caused the restart. By default thepreStartis called, just as in the normal start-up case.

An actor restart replaces only the actual actor object; the contents of the

mailbox is unaffected by the restart, so processing of messages will resume

after the postRestart hook returns. The message

that triggered the exception will not be received again. Any message

sent to an actor while it is being restarted will be queued to its mailbox as

usual.

警告

Be aware that the ordering of failure notifications relative to user messages is not deterministic. In particular, a parent might restart its child before it has processed the last messages sent by the child before the failure. See Discussion: Message Ordering for details.

Stop Hook

After stopping an actor, its postStop hook is called, which may be used

e.g. for deregistering this actor from other services. This hook is guaranteed

to run after message queuing has been disabled for this actor, i.e. messages

sent to a stopped actor will be redirected to the deadLetters of the

ActorSystem.

Identifying Actors via Actor Selection

As described in Actor References, Paths and Addresses, each actor has a unique logical path, which

is obtained by following the chain of actors from child to parent until

reaching the root of the actor system, and it has a physical path, which may

differ if the supervision chain includes any remote supervisors. These paths

are used by the system to look up actors, e.g. when a remote message is

received and the recipient is searched, but they are also useful more directly:

actors may look up other actors by specifying absolute or relative

paths—logical or physical—and receive back an ActorSelection with the

result:

// will look up this absolute path

context.actorSelection("/user/serviceA/aggregator")

// will look up sibling beneath same supervisor

context.actorSelection("../joe")

注釈

It is always preferable to communicate with other Actors using their ActorRef instead of relying upon ActorSelection. Exceptions are

- sending messages using the At-Least-Once Delivery facility

- initiating first contact with a remote system

In all other cases ActorRefs can be provided during Actor creation or initialization, passing them from parent to child or introducing Actors by sending their ActorRefs to other Actors within messages.

The supplied path is parsed as a java.net.URI, which basically means

that it is split on / into path elements. If the path starts with /, it

is absolute and the look-up starts at the root guardian (which is the parent of

"/user"); otherwise it starts at the current actor. If a path element equals

.., the look-up will take a step “up” towards the supervisor of the

currently traversed actor, otherwise it will step “down” to the named child.

It should be noted that the .. in actor paths here always means the logical

structure, i.e. the supervisor.

The path elements of an actor selection may contain wildcard patterns allowing for broadcasting of messages to that section:

// will look all children to serviceB with names starting with worker

context.actorSelection("/user/serviceB/worker*")

// will look up all siblings beneath same supervisor

context.actorSelection("../*")

Messages can be sent via the ActorSelection and the path of the

ActorSelection is looked up when delivering each message. If the selection

does not match any actors the message will be dropped.

To acquire an ActorRef for an ActorSelection you need to send

a message to the selection and use the sender() reference of the reply from

the actor. There is a built-in Identify message that all Actors will

understand and automatically reply to with a ActorIdentity message

containing the ActorRef. This message is handled specially by the

actors which are traversed in the sense that if a concrete name lookup fails

(i.e. a non-wildcard path element does not correspond to a live actor) then a

negative result is generated. Please note that this does not mean that delivery

of that reply is guaranteed, it still is a normal message.

import akka.actor.{ Actor, Props, Identify, ActorIdentity, Terminated }

class Follower extends Actor {

val identifyId = 1

context.actorSelection("/user/another") ! Identify(identifyId)

def receive = {

case ActorIdentity(`identifyId`, Some(ref)) =>

context.watch(ref)

context.become(active(ref))

case ActorIdentity(`identifyId`, None) => context.stop(self)

}

def active(another: ActorRef): Actor.Receive = {

case Terminated(`another`) => context.stop(self)

}

}

You can also acquire an ActorRef for an ActorSelection with

the resolveOne method of the ActorSelection. It returns a Future

of the matching ActorRef if such an actor exists. It is completed with

failure [[akka.actor.ActorNotFound]] if no such actor exists or the identification

didn't complete within the supplied timeout.

Remote actor addresses may also be looked up, if remoting is enabled:

context.actorSelection("akka.tcp://app@otherhost:1234/user/serviceB")

An example demonstrating actor look-up is given in Remoting Sample.

Messages and immutability

IMPORTANT: Messages can be any kind of object but have to be immutable. Scala can’t enforce immutability (yet) so this has to be by convention. Primitives like String, Int, Boolean are always immutable. Apart from these the recommended approach is to use Scala case classes which are immutable (if you don’t explicitly expose the state) and works great with pattern matching at the receiver side.

以下はこのサンプルコードです。

// define the case class

case class Register(user: User)

// create a new case class message

val message = Register(user)

Send messages

Messages are sent to an Actor through one of the following methods.

!means “fire-and-forget”, e.g. send a message asynchronously and return immediately. Also known astell.?sends a message asynchronously and returns aFuturerepresenting a possible reply. Also known asask.

Message ordering is guaranteed on a per-sender basis.

注釈

There are performance implications of using ask since something needs to

keep track of when it times out, there needs to be something that bridges

a Promise into an ActorRef and it also needs to be reachable through

remoting. So always prefer tell for performance, and only ask if you must.

Tell: Fire-forget

This is the preferred way of sending messages. No blocking waiting for a message. This gives the best concurrency and scalability characteristics.

actorRef ! message

If invoked from within an Actor, then the sending actor reference will be

implicitly passed along with the message and available to the receiving Actor

in its sender(): ActorRef member method. The target actor can use this

to reply to the original sender, by using sender() ! replyMsg.

If invoked from an instance that is not an Actor the sender will be

deadLetters actor reference by default.

Ask: Send-And-Receive-Future

The ask pattern involves actors as well as futures, hence it is offered as

a use pattern rather than a method on ActorRef:

import akka.pattern.{ ask, pipe }

import system.dispatcher // The ExecutionContext that will be used

final case class Result(x: Int, s: String, d: Double)

case object Request

implicit val timeout = Timeout(5 seconds) // needed for `?` below

val f: Future[Result] =

for {

x <- ask(actorA, Request).mapTo[Int] // call pattern directly

s <- (actorB ask Request).mapTo[String] // call by implicit conversion

d <- (actorC ? Request).mapTo[Double] // call by symbolic name

} yield Result(x, s, d)

f pipeTo actorD // .. or ..

pipe(f) to actorD

This example demonstrates ask together with the pipeTo pattern on

futures, because this is likely to be a common combination. Please note that

all of the above is completely non-blocking and asynchronous: ask produces

a Future, three of which are composed into a new future using the

for-comprehension and then pipeTo installs an onComplete-handler on the

future to affect the submission of the aggregated Result to another

actor.

Using ask will send a message to the receiving Actor as with tell, and

the receiving actor must reply with sender() ! reply in order to complete the

returned Future with a value. The ask operation involves creating

an internal actor for handling this reply, which needs to have a timeout after

which it is destroyed in order not to leak resources; see more below.

警告

To complete the future with an exception you need send a Failure message to the sender. This is not done automatically when an actor throws an exception while processing a message.

try {

val result = operation()

sender() ! result

} catch {

case e: Exception =>

sender() ! akka.actor.Status.Failure(e)

throw e

}

If the actor does not complete the future, it will expire after the timeout

period, completing it with an AskTimeoutException. The timeout is

taken from one of the following locations in order of precedence:

- explicitly given timeout as in:

import scala.concurrent.duration._

import akka.pattern.ask

val future = myActor.ask("hello")(5 seconds)

- implicit argument of type

akka.util.Timeout, e.g.

import scala.concurrent.duration._

import akka.util.Timeout

import akka.pattern.ask

implicit val timeout = Timeout(5 seconds)

val future = myActor ? "hello"

See Futures for more information on how to await or query a future.

The onComplete, onSuccess, or onFailure methods of the Future can be

used to register a callback to get a notification when the Future completes, giving

you a way to avoid blocking.

警告

When using future callbacks, such as onComplete, onSuccess, and onFailure,

inside actors you need to carefully avoid closing over

the containing actor’s reference, i.e. do not call methods or access mutable state

on the enclosing actor from within the callback. This would break the actor

encapsulation and may introduce synchronization bugs and race conditions because

the callback will be scheduled concurrently to the enclosing actor. Unfortunately

there is not yet a way to detect these illegal accesses at compile time.

See also: アクターと共有可変状態

Forward message

You can forward a message from one actor to another. This means that the original sender address/reference is maintained even though the message is going through a 'mediator'. This can be useful when writing actors that work as routers, load-balancers, replicators etc.

target forward message

Receive messages

An Actor has to implement the receive method to receive messages:

This method returns a PartialFunction, e.g. a ‘match/case’ clause in

which the message can be matched against the different case clauses using Scala

pattern matching. Here is an example:

import akka.actor.Actor

import akka.actor.Props

import akka.event.Logging

class MyActor extends Actor {

val log = Logging(context.system, this)

def receive = {

case "test" => log.info("received test")

case _ => log.info("received unknown message")

}

}

Reply to messages

If you want to have a handle for replying to a message, you can use

sender(), which gives you an ActorRef. You can reply by sending to

that ActorRef with sender() ! replyMsg. You can also store the ActorRef

for replying later, or passing on to other actors. If there is no sender (a

message was sent without an actor or future context) then the sender

defaults to a 'dead-letter' actor ref.

case request =>

val result = process(request)

sender() ! result // will have dead-letter actor as default

Receive timeout

The ActorContext setReceiveTimeout defines the inactivity timeout after which

the sending of a ReceiveTimeout message is triggered.

When specified, the receive function should be able to handle an akka.actor.ReceiveTimeout message.

1 millisecond is the minimum supported timeout.

Please note that the receive timeout might fire and enqueue the ReceiveTimeout message right after another message was enqueued; hence it is not guaranteed that upon reception of the receive timeout there must have been an idle period beforehand as configured via this method.

Once set, the receive timeout stays in effect (i.e. continues firing repeatedly after inactivity periods). Pass in Duration.Undefined to switch off this feature.

import akka.actor.ReceiveTimeout

import scala.concurrent.duration._

class MyActor extends Actor {

// To set an initial delay

context.setReceiveTimeout(30 milliseconds)

def receive = {

case "Hello" =>

// To set in a response to a message

context.setReceiveTimeout(100 milliseconds)

case ReceiveTimeout =>

// To turn it off

context.setReceiveTimeout(Duration.Undefined)

throw new RuntimeException("Receive timed out")

}

}

Messages marked with NotInfluenceReceiveTimeout will not reset the timer. This can be useful when

ReceiveTimeout should be fired by external inactivity but not influenced by internal activity,

e.g. scheduled tick messages.

Stopping actors

Actors are stopped by invoking the stop method of a ActorRefFactory,

i.e. ActorContext or ActorSystem. Typically the context is used for stopping

the actor itself or child actors and the system for stopping top level actors. The actual

termination of the actor is performed asynchronously, i.e. stop may return before

the actor is stopped.

class MyActor extends Actor {

val child: ActorRef = ???

def receive = {

case "interrupt-child" =>

context stop child

case "done" =>

context stop self

}

}

Processing of the current message, if any, will continue before the actor is stopped,

but additional messages in the mailbox will not be processed. By default these

messages are sent to the deadLetters of the ActorSystem, but that

depends on the mailbox implementation.

Termination of an actor proceeds in two steps: first the actor suspends its

mailbox processing and sends a stop command to all its children, then it keeps

processing the internal termination notifications from its children until the last one is

gone, finally terminating itself (invoking postStop, dumping mailbox,

publishing Terminated on the DeathWatch, telling

its supervisor). This procedure ensures that actor system sub-trees terminate

in an orderly fashion, propagating the stop command to the leaves and

collecting their confirmation back to the stopped supervisor. If one of the

actors does not respond (i.e. processing a message for extended periods of time

and therefore not receiving the stop command), this whole process will be

stuck.

Upon ActorSystem.terminate, the system guardian actors will be

stopped, and the aforementioned process will ensure proper termination of the

whole system.

The postStop hook is invoked after an actor is fully stopped. This

enables cleaning up of resources:

override def postStop() {

// clean up some resources ...

}

注釈

Since stopping an actor is asynchronous, you cannot immediately reuse the

name of the child you just stopped; this will result in an

InvalidActorNameException. Instead, watch the terminating

actor and create its replacement in response to the Terminated

message which will eventually arrive.

PoisonPill

You can also send an actor the akka.actor.PoisonPill message, which will

stop the actor when the message is processed. PoisonPill is enqueued as

ordinary messages and will be handled after messages that were already queued

in the mailbox.

Graceful Stop

gracefulStop is useful if you need to wait for termination or compose ordered

termination of several actors:

import akka.pattern.gracefulStop

import scala.concurrent.Await

try {

val stopped: Future[Boolean] = gracefulStop(actorRef, 5 seconds, Manager.Shutdown)

Await.result(stopped, 6 seconds)

// the actor has been stopped

} catch {

// the actor wasn't stopped within 5 seconds

case e: akka.pattern.AskTimeoutException =>

}

object Manager {

case object Shutdown

}

class Manager extends Actor {

import Manager._

val worker = context.watch(context.actorOf(Props[Cruncher], "worker"))

def receive = {

case "job" => worker ! "crunch"

case Shutdown =>

worker ! PoisonPill

context become shuttingDown

}

def shuttingDown: Receive = {

case "job" => sender() ! "service unavailable, shutting down"

case Terminated(`worker`) =>

context stop self

}

}

When gracefulStop() returns successfully, the actor’s postStop() hook

will have been executed: there exists a happens-before edge between the end of

postStop() and the return of gracefulStop().

In the above example a custom Manager.Shutdown message is sent to the target

actor to initiate the process of stopping the actor. You can use PoisonPill for

this, but then you have limited possibilities to perform interactions with other actors

before stopping the target actor. Simple cleanup tasks can be handled in postStop.

警告

Keep in mind that an actor stopping and its name being deregistered are

separate events which happen asynchronously from each other. Therefore it may

be that you will find the name still in use after gracefulStop()

returned. In order to guarantee proper deregistration, only reuse names from

within a supervisor you control and only in response to a Terminated

message, i.e. not for top-level actors.

Become/Unbecome

Upgrade

Akka supports hotswapping the Actor’s message loop (e.g. its implementation) at

runtime: invoke the context.become method from within the Actor.

become takes a PartialFunction[Any, Unit] that implements the new

message handler. The hotswapped code is kept in a Stack which can be pushed and

popped.

警告

Please note that the actor will revert to its original behavior when restarted by its Supervisor.

To hotswap the Actor behavior using become:

class HotSwapActor extends Actor {

import context._

def angry: Receive = {

case "foo" => sender() ! "I am already angry?"

case "bar" => become(happy)

}

def happy: Receive = {

case "bar" => sender() ! "I am already happy :-)"

case "foo" => become(angry)

}

def receive = {

case "foo" => become(angry)

case "bar" => become(happy)

}

}

This variant of the become method is useful for many different things,

such as to implement a Finite State Machine (FSM, for an example see Dining

Hakkers). It will replace the current behavior (i.e. the top of the behavior

stack), which means that you do not use unbecome, instead always the

next behavior is explicitly installed.

The other way of using become does not replace but add to the top of

the behavior stack. In this case care must be taken to ensure that the number

of “pop” operations (i.e. unbecome) matches the number of “push” ones

in the long run, otherwise this amounts to a memory leak (which is why this

behavior is not the default).

case object Swap

class Swapper extends Actor {

import context._

val log = Logging(system, this)

def receive = {

case Swap =>

log.info("Hi")

become({

case Swap =>

log.info("Ho")

unbecome() // resets the latest 'become' (just for fun)

}, discardOld = false) // push on top instead of replace

}

}

object SwapperApp extends App {

val system = ActorSystem("SwapperSystem")

val swap = system.actorOf(Props[Swapper], name = "swapper")

swap ! Swap // logs Hi

swap ! Swap // logs Ho

swap ! Swap // logs Hi

swap ! Swap // logs Ho

swap ! Swap // logs Hi

swap ! Swap // logs Ho

}

Encoding Scala Actors nested receives without accidentally leaking memory

See this Unnested receive example.

Stash

The Stash trait enables an actor to temporarily stash away messages

that can not or should not be handled using the actor's current

behavior. Upon changing the actor's message handler, i.e., right

before invoking context.become or context.unbecome, all

stashed messages can be "unstashed", thereby prepending them to the actor's

mailbox. This way, the stashed messages can be processed in the same

order as they have been received originally.

注釈

The trait Stash extends the marker trait

RequiresMessageQueue[DequeBasedMessageQueueSemantics] which

requests the system to automatically choose a deque based

mailbox implementation for the actor. If you want more control over the

mailbox, see the documentation on mailboxes: Mailboxes.

Here is an example of the Stash in action:

import akka.actor.Stash

class ActorWithProtocol extends Actor with Stash {

def receive = {

case "open" =>

unstashAll()

context.become({

case "write" => // do writing...

case "close" =>

unstashAll()

context.unbecome()

case msg => stash()

}, discardOld = false) // stack on top instead of replacing

case msg => stash()

}

}

Invoking stash() adds the current message (the message that the

actor received last) to the actor's stash. It is typically invoked

when handling the default case in the actor's message handler to stash

messages that aren't handled by the other cases. It is illegal to

stash the same message twice; to do so results in an

IllegalStateException being thrown. The stash may also be bounded

in which case invoking stash() may lead to a capacity violation,

which results in a StashOverflowException. The capacity of the

stash can be configured using the stash-capacity setting (an Int) of the

mailbox's configuration.

Invoking unstashAll() enqueues messages from the stash to the

actor's mailbox until the capacity of the mailbox (if any) has been

reached (note that messages from the stash are prepended to the

mailbox). In case a bounded mailbox overflows, a

MessageQueueAppendFailedException is thrown.

The stash is guaranteed to be empty after calling unstashAll().

The stash is backed by a scala.collection.immutable.Vector. As a

result, even a very large number of messages may be stashed without a

major impact on performance.

警告

Note that the Stash trait must be mixed into (a subclass of) the

Actor trait before any trait/class that overrides the preRestart

callback. This means it's not possible to write

Actor with MyActor with Stash if MyActor overrides preRestart.

Note that the stash is part of the ephemeral actor state, unlike the

mailbox. Therefore, it should be managed like other parts of the

actor's state which have the same property. The Stash trait’s

implementation of preRestart will call unstashAll(), which is

usually the desired behavior.

注釈

If you want to enforce that your actor can only work with an unbounded stash,

then you should use the UnboundedStash trait instead.

Killing an Actor

You can kill an actor by sending a Kill message. This will cause the actor

to throw a ActorKilledException, triggering a failure. The actor will

suspend operation and its supervisor will be asked how to handle the failure,

which may mean resuming the actor, restarting it or terminating it completely.

See What Supervision Means for more information.

Use Kill like this:

// kill the 'victim' actor

victim ! Kill

Actors and exceptions

It can happen that while a message is being processed by an actor, that some kind of exception is thrown, e.g. a database exception.

What happens to the Message

If an exception is thrown while a message is being processed (i.e. taken out of its mailbox and handed over to the current behavior), then this message will be lost. It is important to understand that it is not put back on the mailbox. So if you want to retry processing of a message, you need to deal with it yourself by catching the exception and retry your flow. Make sure that you put a bound on the number of retries since you don't want a system to livelock (so consuming a lot of cpu cycles without making progress). Another possibility would be to have a look at the PeekMailbox pattern.

What happens to the mailbox

If an exception is thrown while a message is being processed, nothing happens to the mailbox. If the actor is restarted, the same mailbox will be there. So all messages on that mailbox will be there as well.

What happens to the actor

If code within an actor throws an exception, that actor is suspended and the supervision process is started (see Supervision and Monitoring). Depending on the supervisor’s decision the actor is resumed (as if nothing happened), restarted (wiping out its internal state and starting from scratch) or terminated.

Extending Actors using PartialFunction chaining

Sometimes it can be useful to share common behavior among a few actors, or compose one actor's behavior from multiple smaller functions.

This is possible because an actor's receive method returns an Actor.Receive, which is a type alias for PartialFunction[Any,Unit],

and partial functions can be chained together using the PartialFunction#orElse method. You can chain as many functions as you need,

however you should keep in mind that "first match" wins - which may be important when combining functions that both can handle the same type of message.

For example, imagine you have a set of actors which are either Producers or Consumers, yet sometimes it makes sense to

have an actor share both behaviors. This can be easily achieved without having to duplicate code by extracting the behaviors to

traits and implementing the actor's receive as combination of these partial functions.

trait ProducerBehavior {

this: Actor =>

val producerBehavior: Receive = {

case GiveMeThings =>

sender() ! Give("thing")

}

}

trait ConsumerBehavior {

this: Actor with ActorLogging =>

val consumerBehavior: Receive = {

case ref: ActorRef =>

ref ! GiveMeThings

case Give(thing) =>

log.info("Got a thing! It's {}", thing)

}

}

class Producer extends Actor with ProducerBehavior {

def receive = producerBehavior

}

class Consumer extends Actor with ActorLogging with ConsumerBehavior {

def receive = consumerBehavior

}

class ProducerConsumer extends Actor with ActorLogging

with ProducerBehavior with ConsumerBehavior {

def receive = producerBehavior.orElse[Any, Unit](consumerBehavior)

}

// protocol

case object GiveMeThings

final case class Give(thing: Any)

Instead of inheritance the same pattern can be applied via composition - one would simply compose the receive method using partial functions from delegates.

Initialization patterns

The rich lifecycle hooks of Actors provide a useful toolkit to implement various initialization patterns. During the

lifetime of an ActorRef, an actor can potentially go through several restarts, where the old instance is replaced by

a fresh one, invisibly to the outside observer who only sees the ActorRef.

One may think about the new instances as "incarnations". Initialization might be necessary for every incarnation

of an actor, but sometimes one needs initialization to happen only at the birth of the first instance when the

ActorRef is created. The following sections provide patterns for different initialization needs.

Initialization via constructor

Using the constructor for initialization has various benefits. First of all, it makes it possible to use val fields to store

any state that does not change during the life of the actor instance, making the implementation of the actor more robust.

The constructor is invoked for every incarnation of the actor, therefore the internals of the actor can always assume

that proper initialization happened. This is also the drawback of this approach, as there are cases when one would

like to avoid reinitializing internals on restart. For example, it is often useful to preserve child actors across

restarts. The following section provides a pattern for this case.

Initialization via preStart

The method preStart() of an actor is only called once directly during the initialization of the first instance, that

is, at creation of its ActorRef. In the case of restarts, preStart() is called from postRestart(), therefore

if not overridden, preStart() is called on every incarnation. However, by overriding postRestart() one can disable

this behavior, and ensure that there is only one call to preStart().

One useful usage of this pattern is to disable creation of new ActorRefs for children during restarts. This can be

achieved by overriding preRestart():

override def preStart(): Unit = {

// Initialize children here

}

// Overriding postRestart to disable the call to preStart()

// after restarts

override def postRestart(reason: Throwable): Unit = ()

// The default implementation of preRestart() stops all the children

// of the actor. To opt-out from stopping the children, we

// have to override preRestart()

override def preRestart(reason: Throwable, message: Option[Any]): Unit = {

// Keep the call to postStop(), but no stopping of children

postStop()

}

Please note, that the child actors are still restarted, but no new ActorRef is created. One can recursively apply

the same principles for the children, ensuring that their preStart() method is called only at the creation of their

refs.

For more information see What Restarting Means.

Initialization via message passing

There are cases when it is impossible to pass all the information needed for actor initialization in the constructor,

for example in the presence of circular dependencies. In this case the actor should listen for an initialization message,

and use become() or a finite state-machine state transition to encode the initialized and uninitialized states

of the actor.

var initializeMe: Option[String] = None

override def receive = {

case "init" =>

initializeMe = Some("Up and running")

context.become(initialized, discardOld = true)

}

def initialized: Receive = {

case "U OK?" => initializeMe foreach { sender() ! _ }

}

If the actor may receive messages before it has been initialized, a useful tool can be the Stash to save messages

until the initialization finishes, and replaying them after the actor became initialized.

警告

This pattern should be used with care, and applied only when none of the patterns above are applicable. One of

the potential issues is that messages might be lost when sent to remote actors. Also, publishing an ActorRef in

an uninitialized state might lead to the condition that it receives a user message before the initialization has been

done.

Contents